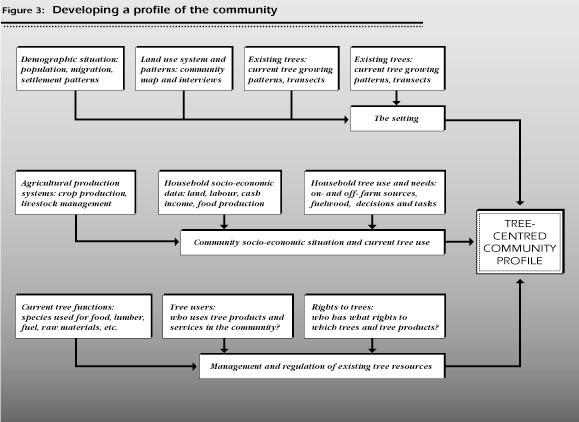

This section is designed to help the field worker gain a thorough knowledge and understanding of the community and its current tree use practices. It will provide information that is needed for determining the options and constraints within the community in the selection of tree species (see Figure 3).

The size, composition and distribution of the population of the community are important factors in determining:

These elements can have a significant influence on species choice. Sample Worksheet 1 provides a framework and suggestions for gathering population information.

ObjectiveTo obtain information on the size, density, composition and migration patterns of the community's population. |

Population size and density: You can usually find some information on the population of the community. Currently almost all countries have a national census about every 10 years. Since the census is used to provide government agencies with population information, regional, district, or even community level information is usually available.

The common problem with census data is that it might not reflect the current population - if the census is 7 or 8 years old the population in the community could be substantially larger than the census figures. However, remember that for your purpose all that is needed is an approximate figure, not a complete and accurate count.

You can easily update the old census figures: Take the latest census information as the base figure and use the annual growth rate to increase the population year by year. Growth rates are expressed in percentages, for example, 2.5% a year. National growth rates are readily obtainable; local rates may require a search through census records.

Migration: Information on migration patterns is often included in census reports and surveys. Other sources are university or research institute studies, project documents, and government ministries of (according to the country) settlement, housing, health, agriculture, etc. National census data and local lists can be used to analyze what is occurring in the local community, but you will have to supplement the secondary sources with interviews of community members.

Village lists: In some countries village leaders are required to keep a list of all households and their members. These village lists are usually the best source of information that you can have since they are extremely useful not only for estimating the population of the community, but also for providing information on household size, the gender of the household head, and absent community members. The lists can also serve as the basis for choosing households which represent the different user groups.

What if there are no village lists or census information? There is a simple four step method to estimate the population and population density of the community that can (and should) be done quickly in combination with other activities (see Box on page 20).

Migration. While gathering information on the number of residents in a household (either when interviewing the household members themselves, or when collecting household information during transects or mapping), ask if anyone in the household is residing elsewhere, and if so, for how long and for what reason.

Again, the objective is to understand the general pattern of population movement into and out of the community, not the actual number of individuals involved in migration. Identification of a pattern of young male out-migration to urban areas leading to a relatively high proportion of female-headed households is extremely useful; an accurate count of males living outside the community, which would require much more time and effort, is not very useful.

Estimating Population DensitySTEP 1: Obtain an approximate count of the number of households and area (km2) of the community. Walk around the community and make a count of households you observe and make an estimate of the community's area. You can combine this activity with mapping and transects (Worksheets 2 and 4). There may be recognized community boundaries (road, river, mountain ridge) that will help you in your estimate. Example:

STEP 2: Estimate the average number of individuals in the household. While doing the transects and mapping, ask the community member(s) accompanying you who lives in the households that you encounter. In a densely settled larger community rather than for every household, information could be asked of every third or fifth household. The goal is to have enough information to be able to estimate the average number of household members. An average is obtained by dividing the total number of residents by the number of households questioned. Example:

STEP 3: Multiply the number of households by the average number of residents per household. The result is the estimated population of the community. Example:Each household has about 4.7 residents: STEP 4: Divide the estimated population by the estimated area (km2) of the community. The result is the estimated population density of the community. 1410 community members / 10 km2 = 141 persons/km2 |

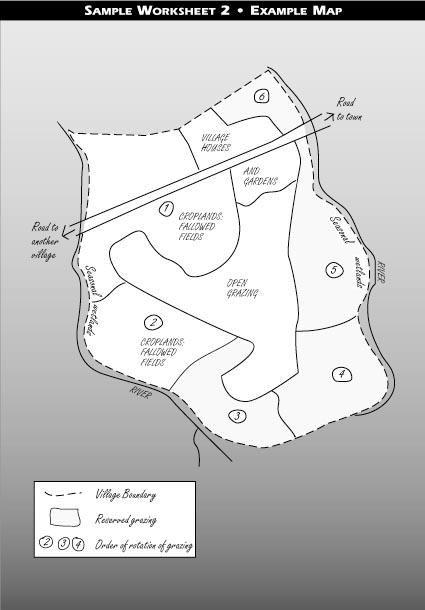

It is important to have an estimate of the proportion of the land in the community under the various types of land use (annual crops, perennial crops, fallow, pasture, etc.). This section provides instructions on how to do a map of the community, which can be done at the same time as Worksheet 1 on demographic data or during preparation for the transect activity in Worksheet 4. Note that the map is to show only estimates of area under the various types of a land use and should be based on observation and participatory mapping, in which the community members help to draw the map.

ObjectiveTo map out the current distribution, arrangement and proportion of land under each major type of land use and its location within the area being utilized by the community. |

Maps may be available in development project documents, district reports, research institution reports, or through the extension services. Aerial photographs are extremely useful, and are becoming readily available in many countries.

If there is little information from secondary sources available, you can do an estimate of the proportion of the land under each major type of land use through observation and mapping (drawing a rough map of the village area). Ideally, secondary sources should always be verified by field observation.

If possible, mapping should be combined with collecting information on population (Worksheet 1) and during transects of the community (Worksheet 4).

Using these sources, carry out the following steps:

Important: make special note of topographical features (such as hills, valleys, rivers and roads) so you will have some guidelines when transferring their map to yours.

In addition to the map, it is useful to get a description of the land use system from community members and leaders. The worksheet in this section is a short checklist that provides the description of the map which the community has prepared in the preceding section.

ObjectiveTo complement the map by describing the general land use pattern and inequities within the community in access to landed resources. |

This is general information which describes the majority of the households in the community. Government documents and project reports should provide enough information for you to be able to understand the land use system, distribution of resources, and settlement pattern. However, be careful to avoid using sources with a negative or biased view of certain systems which distorts the information.

In East Africa, land use systems with a large number of livestock were commonly classified as communities based on "livestock with very little or no cropping" until it was recognized that although livestock were culturally more valued than crops, conferring income and status on the owner, in many such communities the bulk of the food was obtained through crop production. This type of community should be classified as "livestock with annual crops (food)."

Part of the information for this description should be available from the community map (see above). Your observations and informal group and community discussions should provide the remaining information.

A thorough knowledge of current tree growing patterns in the community is obviously very important when deciding to plant new trees. You can use two methods to obtain this information:

A transect is a line drawn through the map of the area being explored, along which you walk (or ride or drive) together with one or more community members, while making specific detailed observations. In this case, these observations are particularly concerned with the terrain and micro-ecological zones to understand where certain trees are planted or retained by the community, and how they are arranged. An Example Transect is given in the worksheet below, and another example from a very different site can be found in Appendix 2.

ObjectiveTo identify, through direct observation in the landscape, the general pattern and current practice of tree-growing as it is integrated into the land use system. |

Athough there may be descriptions of tree growing patterns available in secondary sources, the best information will be obtained by walking through the community during the transects.

The transect itself is a method for obtaining information from the community, through observation assisted by community sources. Making a series of transects is one of the best ways of gathering information on the general tree growing patterns in the community.

To make a transect, a route should be chosen across the community territory which gives the best representation of the land use patterns and different terrains present in the area. The transect is then made by following this predetermined route on foot, animal, cart or motor vehicle (the slower, the better for close observation).

You need to be accompanied on this excercise by one or two knowledgeable community members, if possible including both a man and a woman. During the walk, you will be noting your observations as well as asking questions of your informants relative to to the area being crossed. Clearly explain the purpose of the transect - it would not be surprising for people to be concerned when they see a person walking through their fields making sketches!

After completion of data collection in the field, these field notes will be transcribed onto a sheet of paper in the form of a sketch showing a cross-section of the territory. A descriptive name is given to each different type of micro-environment traversed (fields, forest, village, etc. - see the example in Worksheet 4 below). Under each one, the following features are described:

The purpose of the transect is not to be able to draw a precise map. The goal is to produce a sketch which broadly shows the species, location, and arrangement of trees in the community.

This is also a good opportunity to gather information about the production systems and the households that you pass while walking your route (see Worksheets 7, 9 and 10).

The worksheet below should be used to consolidate information gathered from secondary sources, observation and transects, and used as a basis for further community discussions concerning the location of trees in the community. The worksheet provides a framework for listing the identified trees and niches, and when complete it should contain more tree species, niches, and descriptive information than can be found during the transects.

ObjectiveTo gather information from community members on current tree planting or retention locations and practices, and also on tree species and use. |

There may be government documents or records of government policy which will aid in the analysis of current tree planting patterns. It is important to determine if the tree growing patterns in the community are the result of local preference, or of government policy, as in the following example from Dewees (1991).

In the past in Kenya, colonial government agricultural policy strongly discouraged trees being retained in crop fields. Farmers were told to cut down all trees in their fields, so that they would take on the appearance (and, it was hoped, the productivity) of "modern" fields. Separate woodlots of black wattle (Acacia mearnsii) were also encouraged, primarily to provide income to pay taxes. Both of these policies had a profound impact on tree planting and retaining practices in this country.

Your observations and discussions within the community will be the most important source of information on where trees are found in the current community land use system. You should use the worksheet below to consolidate what you have already observed during mapping and transects (Worksheets 2 and 3), and to gather additional information through informal discussion.

You should also discuss with members of the community past and current government policies concerning where trees could be planted or retained. Community leaders will probably be the best source of information on the implementation of government policies in the area.

The physical environment of the community establishes the range of physical conditions for the potential tree species. Information can be collected from secondary and community sources on the amount of rainfall, rainfall patterns, temperature, wind and other climatic factors, and on soil conditions. Secondary sources generally supply this type of information on the scale of a relatively large area (province, county, district, etc.) which may not reflect the local physical environment of a community or variations within the community area. Because of this, you will need to confirm this type of information in the field. The worksheet below provides a framework for gathering information on the physical environment.

ObjectiveTo collect the information concerning the physical environment of the community. Of special interest is information which relates to tree growing: patterns of rainfall, temperature and soils. |

Information concerning meteorology is generally available in every country. The limitation of this source of information is that it is usually expressed in averages for rather large areas, unless there is a weather station close by the community.

Useful information may be available on the scientific classification of the soils in the area in government documents, project reports, etc. although it may be very broad and not include specific information on the site.

Climate and soils can vary over rather small distances (especially in hilly or mountainous areas), so secondary sources should be verified in the field. Who would know more about the physical environment of an area than those who live there? Although community members may not be able to tell you the precise amount of rainfall or pH of the soil, they can usually provide excellent relative information, eg. the annual distribution of rainfall and what does or does not grow well at a site.

Climate: One of the best methods for obtaining information about the reliability and pattern of local rainfall is a rainfall calendar of the year made by members of the community (see Box on page 38).

Who should you ask?

Choosing the particular group can be done informally: several men returning from their fields together; several women going to fetch water or on their way to market. The interview should be done in a place where people will feel comfortable. It should be in a semi-public area - the homestead area (compound) of a household usually works well.

Drawing a Rainfall CalendarAsk for a calendar of the year to be drawn on the ground. This allows people to feel free to change it, which they might not be willing to do once it is drawn on a piece of paper. Although dividing the year into months such as January, February, etc., is quite common in most areas, it might be best to use the traditional calendar, with the local divisions and names for months, seasons, etc. Then ask for the months (or the local divisions) to be filled with beans, pebbles, shells or other markers, which represent rain. Rather than the absolute amount of rainfall, a precise measurement which probably will not be known, ask for relative amounts. For example: "During which month does it rain the most? Which is the next most?" And so on. The more pebbles within the month, the more rain; the fewer the pebbles, the less rain. This is a rainfall calendar of a community in a region classified in maps and government documents as a "monsoon" climate with a rainy season from May to mid-October and dry season from mid-October to April. In the community, a different pattern was described, as shown in the calendar below, drawn with the community members. There was some disagreement among participants in the discussion over the relative amount of rainfall in November and December, especially since during the current year there had been almost no rain during those months. This is the calendar that was drawn (dots represent pebbles: the more pebbles the more rainfall; the information has been transferred to a Western calendar):

|

Soils: The past experience of tree growing in the community provides valuable information regarding the suitability of certain trees for local conditions. There will usually be some classification of soils within the community. It may be based on color, textures, or other characteristics.

Your task is not to do a study of the local soil classification system. You will only need to ask community members two very specific questions:

On what soils do trees grow best?

On what soils do trees not grow well?

This local knowledge should be incorporated into the information on the physical environment of the community and confirmed by your observations in the community.

It is important to understand the agricultural production systems of the community in order to understand the gaps which may be filled by trees and tree products, as well as the most appropriate places in which to integrate tree planting and management. This section explores the major crops grown and livestock raised, for food or cash, and management practices of the community. The worksheet below provides a framework for gathering this information.

ObjectiveTo identify the major production systems of the community, and in particular the cultivation and management practices of the predominant crops and livestock types. |

It should be possible to find government agricultural statistics, project preparation documents, and other sources which give a general description of the crops and management practices, marketing opportunities, and livestock activities. If there are cooperatives or marketing boards, they will have records which can be very useful. Any nearby agricultural colleges or research stations will also be rich sources of information on local production systems.

Observation is important. What do you observe in the community? What crops do you see growing in the fields, being sold in the market, and being transported in trucks? Do you see livestock in combined herds or family herds? Where is livestock grazed?

In talking to farmers, keep in mind that although they may be reluctant to say how much was harvested or sold, most farmers are very willing to talk of the problems that they encounter in crop production and marketing. If certain practices (such as shifting cultivation) are banned, farmers may not be willing to discuss their use of it as a cropping practice. However, they might be willing to discuss why such bans should be lifted.

Remember that you need to identify the general pattern for the community. While there may be significant variation from household to household (which should be noted), it is the general pattern that emerges which is of more importance.

Although some of the same questions will be asked of both the community and the household, the household profile uses selected households to represent identified groups within the community, rather than seeking community-wide patterns.

Information is gathered from a representative sample of households concerning household members, farm resources, labour, livestock, income, location and spatial arrangement of on-farm trees, on- and off-farm tree use, fuelwood use, and wood supplies. The worksheets which follow below provide a framework for the gathering of household information.

Household composition: It is important to establish which unit in a community resides together, shares agricultural/tree responsibility and rights, and provides labour. In some regions a separate house indicates a household that has its own gardens and fields with the household members making the decisions as to which crops, trees, etc., will be planted. However, in other regions families sharing the same house may have separate fields or families residing in their own houses may have combined fields with other families and joint decision-making. In regions with many ethnic groups, castes, etc., you should verify information from secondary sources through discussions with community members.

Which households? You cannot interview all the households in the entire community. You have to choose a few households that will accurately represent the community (see Box on page 50). Since you will only be interviewing a small number of households (the sample), you will want to make sure that these households represent groups that will be important in the later analysis of suitable trees for the community.

How many households should you interview? Some researchers suggest that rather than establishing a sample size before interviewing begins, it may be more effective to look at the similarity of responses as interviewing progresses. For example, if you have interviewed five or six households in the same category and the responses have been similar, you can be fairly certain that the answers are valid.

A Simple Method for Choosing a Sample of Households

A sample should reflect the community. From the secondary sources,

observations, and discussions with community members, you should be

able to identify the major groups within the community: ethnic groups,

castes, landlords and landless, salaried employees, wage labourers,

female-headed households, etc. If there are several different groups,

it is important to include all of them in your sample since each will

potentially have its own criteria for tree planting and maintenance.

For example, farmers with large landholdings have more resources than

smallholders, so it could be expected that these two groups would

favour planting different types of trees. In some communities, such as recent resettlements, the great majority of the households may be very similar according to farm size and other criteria, with only a few having more or less than the average (see Case Study 1 in Appendix 1). Such a community would be considered a single major group with further distinctions to be made according to ecological zones and access to facilities (Steps 2 and 3). The community area should be divided according to agro-ecological conditions. Some of the factors to be considered are differences in altitude, rainfall, soils, etc. The more ecological zones, the more potential tree species that can be used by the community. If applicable, you should also divide the community area according to the access to facilities: roads, markets, agricultural extension, etc. Tree species preference may be influenced by access to transport and markets for selling tree products. After determining the socio-economic groups, ecological zones and zones of relative access to facilities, you will choose the specific locations where the survey will be conducted. These should be representative of the community as a whole, including each of the different divisions made in Steps 1 to 3. At each location, a route should be chosen which will pass through the area. Make a rough estimate of how many households are along the route and determine your random interview sequence (every fifth, tenth, etc.). Using this "walking" random sample method entails determining into which socio-economic category the household belongs after the interview. Additional households may have to be interviewed to ensure coverage of all the groups identified in Step 1. |

Nevertheless, you should prepare a basic sample design such as the one above, and determine a reasonable number of interviews which you feel you have the time and resources to complete. This number might also be dependent on how much you already know about the community; the more you know from secondary sources, observations, and discussion, the fewer the number of interviews needed.

Remember that the objective of the household survey is to identify the current practices and needs of the different groups in the community. You want the information not only to be accurate, but also to be gathered quickly from the minimum number of households.

Example of a Sample SectionIn a recent resettlement community where each household had been given about the same amount of land, it was apparent after a short period of time spent in the community that there were three main types of households: relatively well-off households that had more livestock and income from positions in the local government, households that were totally dependent on their farms, and female-headed households in which the spouse was working in another area of the country. There were two major ecological zones in the village area: the hills and the valley. Cutting through both the hills and the valley was a road that was passable for about eight months of the year. The school, village government office, and a small clinic were in the valley near the road. There was a small market in the village every five days, and a larger daily market an hour's walk away. The market was about the same distance from two other communities. It was decided to divide the community by ecological zone and by distance from the village centre and the road. It was divided into four areas: hill site nearest the road and village centre, hill site furthest from the road and centre, valley site nearest the road and center, and valley site furthest from the road and centre. There were about 200 households in the community. It was decided to interview eight households from each site, for a total of 32 households. There was concern that by just walking along a route through each site and stopping at every fifth house or so, the two smallest groups, the well-off and the female-headed households, would not be represented. It was decided to ask at each of the sites for female-headed households and to choose by observation a few prosperous households. This worked well. Two female-headed households, two well-to-do households, and four farm-dependent households were interviewed at each site. |

Be flexible. After five interviews there may be enough similarity in the responses for you to decide to end the interviewing for that group. Or after twenty interviews there may be so little consistency that you may be forced to rethink your group classifications and revise the sampling.

ObjectiveTo gather socio-economic information from a small representative sample of households in the community. This information will be used to determine variation within the community and to identify different user groups. |

There may be previous household surveys of the community by government agencies (such as the census bureau or the office which compiles government statistics), research institutes, or projects. If there have been surveys in the area, the information can be used to provide general household information or to fill in specific gaps, even if it does not cover all the factors that are needed.

Even if secondary sources are available, you will still need to gather information from a small sample of households. Note that the emphasis is on small sample, since you want to get the information that you need as rapidly as possible, not conduct a full-scale research project.

Careful observation is important. When you visit a household, make note of the general land use pattern, crop stands, vegetation cover, distance to roads, trees on-farm, etc. Your observations can serve both as the basis for questions ("How old is this mango tree?"), as well as a on-the-spot check of the answers ("You said that you had not planted any trees, but what about the mango trees around your house?").

The household survey: The survey format below was designed to be a general guideline and includes a wide range of questions. If a question or a section is not applicable to the community, delete it from the survey. Depending on the situation of your particular community, you might decide to ask the questions in a different way, in a different sequence, expand a section, or make other modifications.

Remember that your objective is to obtain the key information from a representative sample of the various types of households in the community, not to interview every household in the community about every topic.

Targeting Extension to the Right UsersIt is not uncommon that the household member who makes the decision to plant a tree is not the household member responsible for caring for it. ExampleThe male heads of household in a community became involved in a tree planting project. The men were given seedlings, which they in turn gave to their wives. During the dry season watering the seedlings became a burden as water had to be carried from streams a half hour or more walk from the house, so most of the seedlings were allowed to die. The project manager belatedly realized that the extension efforts should have included the women as well, since they were the ones in the household who provided the care and maintenance to the seedlings. |

In government documents, previous surveys and project documents, there may be some information on household tree use for such things as fuelwood and construction, and possibly fruit. In addition, information from these sources on household production responsibilities and decision-making, especially when disaggregated by gender, can be helpful in determining who will be involved in planting and care of trees. Information from the Extension Service regarding extension courses offered to farmers on tree care, and the gender of those who attended, is also useful.

In the second part of the household interview (below), there will be opportunities to ask who planted, retained, etc., the trees found on the farm, who uses them, and what trees are considered desirable. During discussions with small same-gender groups, information concerning the different perceptions of tree needs and uses can be gathered to try to find general patterns or group-specific needs.

Observation should also help. Although decision-making is difficult to observe, the results of those decisions are readily apparent. Which family members do you observe involved in tree care? Which family members are involved in the sale of tree products? To validate your observations you should ask several households the questions in the worksheet, and a pattern should be relatively easy to identify. You should ask both male- and female-headed households to see if there are different patterns concerning decision-making and care of seedlings.

In order to establish what needs can be fulfilled by tree species in the future, it is necessary to first establish what are the current functions of trees. Gathering information concerning trees in the community can provide you with the information needed for an analysis of the current role of trees. When combined with the priority needs of the community, this analysis should result in the identification of potential tree species for planting. You must identify which trees are providing what services and products. Sample Worksheet 10 below provides a framework for organizing the information on tree use that you have gathered in the previous worksheets as well as seeking new information where there are still gaps. The information will primarily be obtained through observation and interviewing community members.

ObjectiveTo organize and gather information on the current function of trees in the community. Of interest is not only what the trees provide, but also which trees provide which products and services. To identify which trees are multipurpose (serve more than one function, providing more than one product or service). |

Given the current interest in fuelwood and income provided by tree products, in many countries there will be government documents or project reports that list trees that are used for fuel and income. Information concerning food and fodder products (especially if collected from off-farm sources), medicines, fibre, or services such as soil conservation, windbreaking and shade may be more difficult to find, though occasionally studies do exist from such sources as the anthropology department of a local university or a local research institute.

As with the other aspects of tree growing (niche, spatial location, user group), observation will provide you with a large portion of the information that is needed. Initially, you can gather this information in the course of other activities, especially transects, household surveys, and observations on niche and spatial arrangements.

Although you can observe many of the tree products and services that are available in the community, you will need to ask members of the community to be certain that you have made as complete a list as possible. For example, tree products such as fruit and fiber collected from off-farm sources may not be easily observed. For this information you will need to ask community members, preferably the collectors themselves (the young men who collect tree resins, the women who gather forest fruits, etc.).

The presence of trees does not necessarily mean that they are utilized by the community, or that there is access to the trees by all members of the community. Using the worksheet below, as complete a list as possible should be made of the users of trees and tree products. Observation and the previous worksheets will provide some of the information, but you must also use this worksheet as a checklist in discussions with community leaders and other community members. The worksheet identifies different user groups within broadly defined categories. You should add or delete groups to fit the local situation. Note that the same individual will often be included in several groups, depending on the particular activity and season.

ObjectiveTo identify the users of trees and tree products. The purpose of this activity is to develop a list of user groups in the community, including often overlooked users and interest groups (women, seasonal users, etc.). |

Government and project documents may include an economic analysis of the community that can help in determining where to seek user groups, such as community forestry activity, commerce, agriculture, etc.

Use the worksheet as a guideline to discuss with community leaders and other community members if the activities and users listed below are present in the community.

While moving around in the community, you should be able to observe a range of activities concerning trees and tree products. Observation is important, since many activities are often not mentioned because they are either illegal (such as poaching) or intermittent (such as occasional sale of fruit).

As mentioned above, the same individual may be in several user groups: depending on the season a farmer may also be a forest labourer and a forest product processor, and everyone will probably be a consumer of some type of tree product.

Determine who has rights to which trees and which tree products in the community. Of special concern are the rights of the vulnerable user groups such as the poor, minorities, and women. The worksheet below provides a framework for gathering the information. You will collect information on the tree rights of the state, groups in the community, and subgroups or individuals, as well as on other factors affecting who has what rights to trees.

ObjectiveTo identify who has what rights to which trees and which tree products in the community. |

You should consult the government documents which explain the rights of the state to the trees in the community. In many instances, for example, the state will not "own" the trees, but will have rights to determine what can be done to the trees, such as through the issuance of permits for cutting trees (even on a private landholding). Such rights can have a significant impact on tree growing in a community, and especially on the planting of new trees, so they should be carefully researched.

In many countries there are national laws and regulations, as well as recognized local laws, concerning access to trees and tree resources by both individuals and communities. For example, the use of the forest for grazing may be recognized both for local owners of livestock and for herders who reside outside the community but have an established pattern of seasonal use. Landlords may be granted a certain portion of the products from a tree, the right to refuse tree plantings, or other rights. These laws and regulations should be identified through Secondary Sources, then confirmed at community level.

Existing national and local laws and regulations may not be enforced and should also be verified on location in the field, through discussion with government officials, community leaders and community members. For example, there may be a cutting ban on trees in forest lands, but it may be ignored by the community since forestry department officials rarely visit the area. Such a law would, therefore, have very little impact on the community's use of the forest. As another example, it is not uncommon that national laws such as land reform laws which ban or limit the rights of traditional controllers of resources (landlords, privileged castes, the dominant ethnic group, etc.) are not enforced, and traditional laws or arrangements remain intact in the community.

To identify the rights (both modern and traditional, ignored and enforced), it is necessary to interview a broad sample of community members and leaders. If you conduct the household tree-use survey (Worksheet 9: Household Profile II), the worksheet below can be included in the interview of a selected number of the households from each identified group.

If the household survey is not being conducted, you should carry out the following two simple steps:

User groups: There are many potential user groups in a community. The particular groups will vary from region to region, community to community. You can use the worksheet on tree users (above) to identify user groups. After you have identified the user groups in the community, determine each group's rights to trees (see 2: Part A of the worksheet below). Some examples of possible user groups are: kin groups (lineages, extended families), non-kin corporate groups (village associations, women's groups, etc.), community members (all having the same cluster of rights), landowners, landless, project participants, and so on.

Within a single group, there may be variations in rights to trees. For example, in some regions in Africa there are different household and lineage rights based on gender. Under one such system, women do not have the right to plant or cut trees since this action would imply ownership of both the trees and the land on which they grow, while only men are allowed to own land. Examples of possible subgroups are: men, women, tree retainers, tree planters, borrowers, unmarried youths, and so on. Identify the variations, if any, within the user groups in the community, in order to determine the rights of each subgroup or individual (see 2: Part B of the worksheet below).

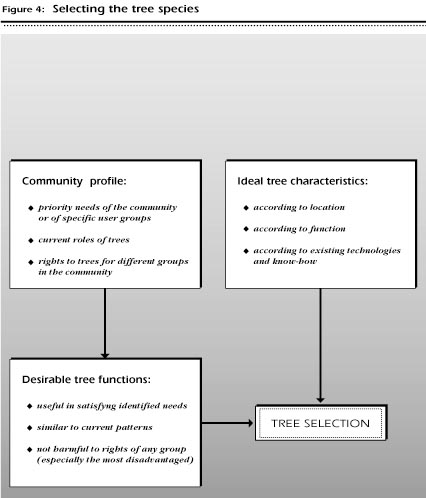

In this step, the field worker and the community together will make the first selection of tree species based on a careful analysis of the information gathered in Step I (see Figure 4). These trees will then be assessed one by one for appropriateness and benefit to the community in Step III.

Now that you have gathered various kinds of information from the community in which you will be planting trees, the next step is to study that information and attempt to answer several questions which will help in selecting the right tree species. Using your notes and the worksheets that you have completed, go through the different questions and points for analysis listed below to develop a more complete picture of the community and its needs and constraints. This analysis will help you organize your information, and then go on to select the most appropriate tree species following the indications in Chapter 5.

With the information collected using the worksheets in the previous chapters, you should now have an in-depth knowledge of the community and an understanding of household composition, farm resources, labour needs, tree growing patterns, decision-making, etc. Using this information, determine:

What is the impact of the population characteristics of the community on tree planting?

Determine whether the size and density of the population is encouraging or discouraging tree planting. For example, is population density so low that all tree and wood needs are met by off-farm sources? Does the settlement pattern not allow large homegardens?

What current land use practices would encourage or discourage tree planting?

Identify characteristics of the current land use practices that would encourage tree planting:

What are the environmental limitations and options for potential tree species?

It should be possible to establish a set of ranges within which the tree species must grow, such as the following:

In a particular community, a selected tree species must be able to become established with 700 mm of rainfall a year distributed in a unimodal pattern during a five month wet season, surviving with virtually no rain for the remainder of the year. It must be able to survive during 90 days of daytime temperatures exceeding 36¡C and daytime temperature ranges of 15¡C. Soils are acidic, shallow and well drained, so the tree species must do well in acidic soils.

What is the current local knowledge concerning trees on- and off-farm, their uses, conditions needed for growth, tree establishment, etc.?

During the activities for the community profile you identified how trees were being utilized by the community. What is the state of knowledge about tree growing? What is the level of familiarity of the community with trees and tree growing? Can you identify any gaps in the local knowledge that hinder tree establishment and maintenance?

What is the relative value of trees within the community? Are livestock or annual crops considered more or less valuable than trees?

Identify the other components of the local economy that are more valued than trees. Livestock may be grazed in fallow fields, even though seedlings will be destroyed, and trees removed from fields if perceived as competing with annual crops. If trees are given a lower priority than other components in the economy, the task of tree selection will be to find species, niches and spatial arrangements that will complement rather than compete with these components.

Analysis of community needs: Determine the priority needs of the community. The results may be consistent and clear (as in Case Study 1 in Appendix 1), or else there may be different priorities of needs for different groups within the community. At this stage determine the priority needs for the community. You will then continue to refine your analysis during the process of determining the right trees. Keep in mind that the more you know about the community, the greater the number of distinct groups you will be able to identify.

You should now know what trees are utilized, how they are used, and where and in what spatial pattern they are planted or retained; you should also know who, both outside and within the community, utilizes the trees and tree products. Using this information also determine:

Which trees are most common? What are their functions?

Identify the most common trees and their functions - food, fuel, fodder, shelter (poles and construction), income, etc. Can you identify a relationship between the frequency of the trees and their functions, eg., most trees are used for food, but perform other valued functions as well, such as fuel from prunings and cash from intermittent sale.

What appears to be the most valued function of trees?

You have determined the functions of the most commonly occurring trees. Are these the most valued, or are the products of less common trees most valued? When community members mention the uses or value of trees, what appears to be highly valued? Note that different trees may be valued by different user groups within the community, so it is necessary to identify the user group and the trees they utilize.

Do planted trees perform a different function from retained trees?

Identify the primary functions of retained and planted trees. Does there appear to be a direct relationship between the functions of trees retained and planted (for example, availability of fuel from existing retained trees allows planted trees to be selected for other functions)?

Is there a relationship between niche and function?

Determine if there is a relationship between location of the planted or retained trees and the uses of the trees, such as when fruit trees are grown around the house, but trees for fodder are grown in the fields.

Are trees planted for environmental improvement (soil improvement, water control, shade, wind shelter)?

Identify if any of the trees currently being grown or retained are being used for environmental improvements (including niche and spatial arrangement). Also note if this is the primary reason for growing that tree, or if the environmental benefit is a secondary function, or even if this function is unrecognized. This distinction is an important one to identify, since a tree grown for several functions would support the choice of other multipurpose trees (trees that can perform a variety of functions).

Are trees or certain species of trees of religious or cultural significance in the community?

It is not uncommon to find that trees are planted or retained and then protected in areas that are sacred to the community, especially grave sites. Certain species may also be considered to be sacred and will be protected. While sometimes these sacred or haunted groves are off-limits to all villagers except religious leaders, in many regions they may be very important off-farm resources for the community and provide fuel (from collected dead wood), food (especially wild fruit and game), and medicine (medicinal plants). If there are sacred forests or trees in the community, identify the user groups and the tree products.

Within the household and within the community, who knows the most about trees, who the least?

Identify if there is a group, gender, age set or other category that knows the most about trees. Within the household it might be the primary caretaker, while at community level it may be the households which are most dependent on tree products. Determine if there is a relationship between user groups and specific knowledge (for example, women may know more about fruit trees, men about trees grown for poles)? Do the poor or landless know more about off-farm trees that can provide food? Do the livestock caretakers know more about trees used for fodder?

Rights to trees: You should also have a clear understanding of who has what rights to trees in the community. Using this knowledge and information from the community and household profiles, also determine:

Do certain groups or individuals have greater or lesser access to trees and tree products in the community than others? If so, identify the groups. What is the basis of inequities in access (class, caste, gender, length of time in community, or others)?

Are trees planted by others perceived to be a threat (will the trees alienate land, establish rights, etc.)?

In some communities an individual can establish long-term rights to land by planting trees. Governments may claim or reclaim land by planting an area with trees (sometimes with community supplied labour). In the community being examined, are trees perceived as a way to establish rights to land (or extend right of exclusion)? If so, you will have to be careful not to suggest niches or spatial arrangements of tree planting that will create or worsen land tenure problems, especially for the most vulnerable groups in the community.

After completing the analysis of community and household needs and the current pattern of trees in the community, it should be possible to determine the functions which would be required of new tree species selected to fit these needs and be appropriate for the community. The appropriateness of the tree species is also determined by considering the current pattern of tree planting in the community. The closer the new tree species is to the current trees, niches and spatial arrangements, the more likely that it will be adopted by the community members: less change often means easier adoption. Radical changes in the level of care, niche or other aspects will require more extension efforts and training, and may also require changes in tenure, rights, and benefit sharing, all of which are difficult to achieve.

Also consider: are new species needed? What the community may need is not a new tree, but better access to trees with which they are familiar. There are definite advantages to continuing with tree species with which the community is already familiar. If it is apparent, after the analysis of community needs and current tree patterns, that the community wants (and needs) more of what it already has, your task might be to obtain planting material, to develop local nurseries, to improve seed distribution, to introduce improved varieties or to demonstrate new niches or spatial arrangements for existing trees.

In the preceding worksheets and analysis, you determined the desired functions of possible new tree species, as well as conditions that should be met by the selected trees. The potential tree species must:

Developing tree species suggestions: After an analysis of these factors, together with the community you should be able to begin to identify specific tree species to plant (see Figure 4). Some of the tree species may already be part of the land use system, others may be new to the community.

Note that it is unlikely that a single tree will exist that performs all the required functions and is suited to all the various conditions listed above. Rather, it will probably be necessary to identify a variety of trees (see Case Study 1 in Appendix 1).

Large farmers may be interested in trees that offer attractive commercial advantages, or that might enable them to exert tenure over large landholdings. This will probably differ from the preferences of a small farmer, who may be more interested in fodder for his animals and food for the household. Gender differences in tree preferences have also been found in many communities. While men may prefer trees that can provide poles and income, women may be more concerned with food production, such as fruit.

As potential tree species are identified, it is important to determine:

In what niche (type of location) within the landscape will the tree be planted?

Locational factors are quite separate from the appropriateness of a tree species. For example, if you have identified fodder production as a high priority need and identified an appropriate tree species, how do you know where the tree should be planted? You must consider who will be the user groups within the community, and the extent of their access to resources. Different groups will have access to different niches in the landscape.

What will be the spatial arrangements of the planted trees?

Decisions regarding the niche in which to plant the tree are also distinct from decisions regarding the spatial arrangements in which trees are to be planted (dispersed, block, linear, multistory, etc.), and whether they are to be grown as a monocrop or in combination with other trees or crops.

Extension and support needs: The extension activities needed for every suggested tree species must also be determined:

Are the seeds or seedlings available?

If the project is responsible for providing the planting material, can it do so? Are the seeds or seedlings available from other sources? Are they available within the community? If planting material is going to be difficult to obtain, another tree species should be considered.

Do the tree species, niches and spatial arrangements require training?

If so, is training personnel available? If training is not available, or if training that would be required is inappropriate (too long, too expensive, or other problems), another tree species should be considered.

When the species, the niche and spatial arrangements have been determined, the right trees have almost been identified. The next step is to reconsider, together with community members, whether the tree matches the identified needs in the community.

ObjectiveTo identify the ideal characteristics which would be desirable for each of the various identified locations in the community. |

As part of the decision-making process, the characteristics or specifications that are necessary for a tree in a certain location should be discussed with the community:

What do community members want most from the tree to be planted?

This is especially needed if an attempt is being made to introduce trees into a new location or new trees into an established location. The checklist below can be used in deciding which characteristics are the most important in the selected species.

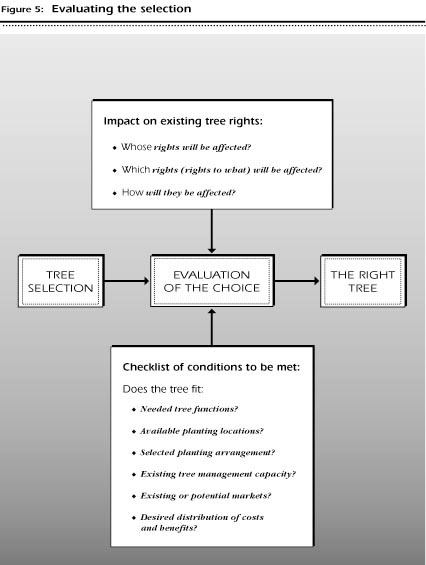

A careful and thorough evaluation of the selected tree species is the key to making successful choices. The community and the field worker must verify that the trees they have selected fit the conditions described in Step I and satisfy the requirements developed in Step II (see Figure 5). It is necessary to be flexible in approaching this evaluation of the choices, and to be ready to reconsider when a selected tree is found not to meet the necessary conditions.

Tree species that have been tentatively identified should be re-examined according to the ways in which their adoption would affect the community.

Whose rights will be affected? Any major change in the use of a resource will provoke change throughout the system of customary rights and obligations that regulate the use of those resources. You should anticipate the likely impact of the proposed change, especially with regard to niche. This impact will affect not only those who are likely to adopt the innovation, but also those who are not interested or may not be able to adopt it, but nevertheless are unable to escape the effects of adoption by others.

The central question is:

Whose rights are likely to be affected by the introduction of a new tree species or a new tree growing practice?

The goal is to be able to anticipate any negative changes which could potentially occur. As with most development projects, while it may be unrealistic to expect all groups to benefit equally, there is the expectation that there should not be a particular user group which is negatively affected. If it appears that one group would suffer a loss if a new tree, niche, etc., was introduced, alternatives should be considered.

Although there are differences from one community to another, several user groups frequently appear to be especially vulnerable to innovation in tree species and niches:

The worksheet below is a matrix that can be used to pinpoint the possible changes in rights that could occur. The rights of different user groups for different tree products are considered. Use the worksheet as a tool in combination with information from observation and discussions with community members to analyze the potential gain or loss of rights with the proposed trees species, niches, and spatial arrangements.

ObjectiveTo assess the impact of the proposed tree species, niches and spatial arrangements on the rights of particular groups in the community. Of special concern is the negative impact that could potentially occur. |

Use this worksheet as a checklist to identify the effects of tree planting on existing land or tree use rights currently held by selected user groups. Information on existing rights should be based on the responses to Worksheet 12 (Tenure and rights to trees) and secondary sources. Using this information, work with community members and leaders to determine the impact on those rights of each selected tree species (including its niche, its products, etc.). The "user groups" and "rights affected" listed in the worksheet should be modified to reflect the community.

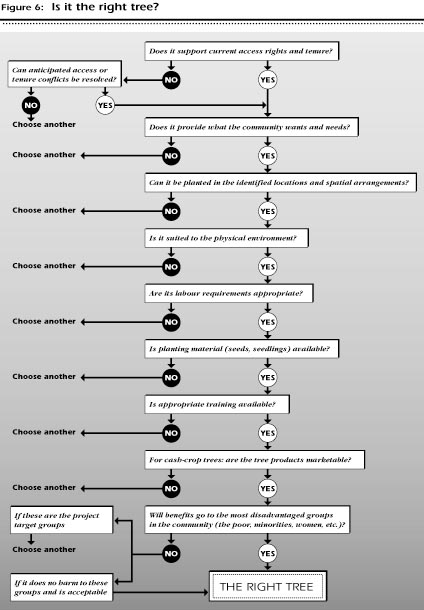

After the tree species selection process has been completed and the tree species have been identified, re-examine the choice. The worksheet below, Is it the right tree?, provides an extensive checklist that reviews the information and decisions that were made during the process of choosing the tree species. The checklist requires a reassessment of function, location, planting arrangement, tree management and rights to products. You should also go through the decision tree in Figure 6.

It is essential that this final assessment be made together with community members. Return to the community members (leaders, women, men, etc.) who have provided information during the tree selection process, and invite them to re-examine the trees, functions, niches, etc., which are suggested.

Finally, after you and the community have gone through a careful process of evaluation of the tree choice, make a final assessment and ask yourselves the question:

Based on your assessment, are the tree species chosen the right trees for the community?

If the answer to this question is not a wholehearted "Yes!", you should return to Chapter 5 and begin the selection process again, or determine if it is possible to change or modify the constraints that resulted in your negative assessment. The selection of tree species is a process, and should be flexible and responsive to information and suggestions!

You should not hesistate to continue repeating this process until you and the community members agree that a particular tree (or several trees) is a right choice. Only when there is general agreement can you finally say, "This is the right tree."

ObjectiveTo determine if all the important factors have been considered in tree species selection. |

This is a checklist of factors that should be considered when tree species are being selected. When a possible tree species has been identified, sit down with community members (women, men, leaders, other groups; together or separately) and go through the checklist to be certain that the following important factors have not been overlooked.