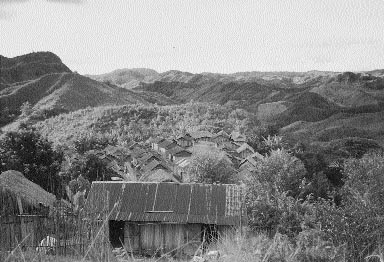

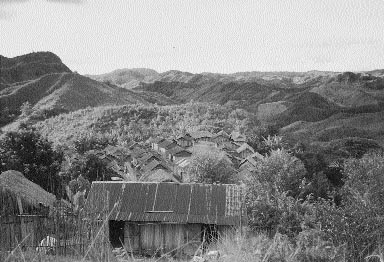

Photo 1: This is a view over the village of Anivorano showing cleared hillsides, once forested.

Community Forestry Case Study 10:

Tree and Land Tenure: Using Rapid Appraisal to Study Natural Resource Management: A case study from Anivorano, Madagascar

by Karen Schoonmaker Freudenberger

This case study illustrates how Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA) can be used to study tenure and resource management issues. It offers just one example of how and why tenure research might be carried out. In this instance, the case study was part of a larger research effort to inform a policy debate in Madagascar on whether (and how) national land legislation should be amended to promote a more sustainable use of the country's resources. This was, in turn, part of a larger programme to devise policies consistent with Madagascar's Environmental Action Plan. In other situations, tenure research might be carried out to help a project better understand how to reinforce villagers' own resource management efforts or whether latent tenure conflicts risk jeopardizing a project's development activities.

This monograph complements earlier Community Forestry publications, particularly Rapid Appraisal of Tree and Land Tenure (Community Forestry Note 5) and Tree and Land Tenure: Rapid Appraisal Tools (Community Forestry Field Manual 4). All three publications emphasize that while there are methodological principles to be followed, there are no formulas for how to do Rapid Appraisal. Readers are asked, therefore, not to use this case as a model for what a Rapid Appraisal should look like, but rather to view it as an example of how the panoply of techniques that comprise the methodology can be combined in a systematic process to gather information on tenure and resource management.

Six chapters tell two stories in one. The first is the tale of how a team of Malagasy and U.S. researchers used RRA to study the complex tenure situation in one Malagasy village. This is the theme of chapters 2 and 3, which take the reader step-by-step through the process that was used to carry out an RRA in the village of Anivorano in June 1993. Chapter 2 discusses the preparations that were made before the team went to the field, and chapter 3 follows the fieldwork chronologically, walking the reader systematically through the activities that were carried out each day.

The second story is about what the team learned as it carried out these techniques in the field. This is the subject of chapters 4 and 5, which assemble the information obtained using different RRA tools into a story about resource management in a hillside village. Interactions between the customary and the state tenure systems are explored as the study attempts to understand the pressures that are leading to the rapid destruction of the forest in Anivorano. It is hoped that with the methodology used to collect the information presented side by side with the study's findings, the reader will get a better feel for RRA's potential to gather practical and usable information of this kind. The principal focus of the case study is on methodological issues, however, and so the last chapter steps back again to put the spotlight on RRA, addressing, in particular, the strengths and limitations of the methodology, using the Anivorano case study to illustrate some of the concerns that have been raised by both practitioners and critics.

Since the late 1980s, both the Government of Madagascar and the donor community have become increasingly concerned about the management of natural resources on the island, which is the fourth largest in the world. Madagascar has a unique ecosystem, host to an extraordinary richness of biological diversity, including nearly 8000 endemic species of flowering plants (Wright 1993). Nevertheless, much of the native vegetation has been lost as forests have been cleared, primarily for logging and agriculture. The diminishing forests of Madagascar are a concern to local people, to the national government and to the international community.

Locally, people's well-being is inextricably tied to the natural resource base, whether used as a source of food, medicines or fuel. Nationally, the government worries about such issues as the effects of deforestation on watersheds, changes in soil fertility that will affect the nation's ability to produce food and the impact on foreign exchange when export products, such as wood, are used up. International concerns focus on questions of the declining biodiversity as plant and animal niches are destroyed through the clearing of ancient forests. Many of Madagascar's plants are highly valued for medicinal purposes in the West as well as locally.

Concern with the declining resource base has led to increased efforts to understand the causes and consequences of forest clearing. Researchers are working to understand the incentives and motivations pushing people to cut forests. With this information, policy makers and development workers can think about how to change the incentives so that communities find it more advantageous to protect forests than to cut them. Information about a community's resource management systems is particularly needed when governments are considering policy changes (e.g. in land and forest codes) that are likely to have a major impact on the incentives and sanctions related to the use of resources. Without understanding the rationale behind local practices, the policy changes may have unintended and even counterproductive effects.

A potential example of such a "backward incentive" was noted in this study. Often people assume, for example, that formal, government-supervised titling of individual land parcels will increase the holder's tenure security. It is supposed that this will, in turn, lead the titled owner to invest and intensify production on agricultural lands, thereby diminishing the practice of more extensive production practices, which put pressure on forests. With the encouragement of some donors, titling is now being considered in Madagascar, and pilot titling programmes have actually begun in some areas. By looking carefully at existing tenure systems and resource-management practices, this study was able to predict that titling of private land-at least in this particular community-was very likely to produce just the opposite effect and lead to even more rapid clearing of the remaining forested area. The reasons for this are discussed in chapter 5.

As Madagascar continues to debate environmental policy reforms, research at many levels has an important role to play in informing the discussion. The case study presented here was part of a larger research project1 investigating land and resource tenure issues and their relationship to natural resource management practices and the conservation of biodiversity in and around Madagascar's protected areas. In addition to this case study village, seven other sites are being studied in order to understand the perspectives and practices of local resource users in different areas of the country. The information gathered from these studies will be discussed in national policy workshops as questions of titling and other resource management policies are reviewed. As ministry officials, representatives of international pharmaceutical companies, wildlife experts, donors and development workers debate these issues, research from RRAs such as this one will help to ensure that the views and concerns of village people are also represented in the debate.

A wide variety of methods can be used to conduct research under diverse conditions in order to meet different objectives. These include highly quantitative techniques, such as survey methods, as well as more qualitative approaches, including anthropological studies. Among the more recent additions to the family of research methodologies are the "participatory" methods, such as Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA) and Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA). The former is most often used by outsiders conducting research in an area, while the latter is more commonly used by local people, sometimes in conjunction with outsiders, conducting research for their own planning purposes.

Every research method, whether quantitative or qualitative, has strengths and weaknesses. The key to getting the best results lies, therefore, in choosing the method best suited to the type of information sought and to the conditions in which the information will be gathered, analysed and used. Often, because different methods are suited to different uses and conditions, it makes sense to combine several methods, using each where it is most appropriate. In the year-long research study (of which this case is just one part) several methods were combined.2 In each of the seven sites studied, at least three research methods were used. In each village, or group of villages, an RRA3 was first conducted. These RRAs typically lasted 7-10 days and provided a core around which other activities took place. (The total time spent in each village was 14-21 days.) In addition to gathering highly useful information, during the RRA the research team built a rapport with the community which facilitated the other research activities.

What is RRA?Rapid Rural Appraisal is a qualitative, participatory research methodology, most often used to gather and analyse information in rural communities. In RRA, multidisciplinary teams of researchers from different backgrounds conduct studies of carefully defined issues, generally in short, intensive field studies. RRA uses a variety of tools and techniques to gather information. All its tools are designed to promote the participation of local people in both the collection and the analysis of information. The tools approach questions from different angles, however. Some are particularly helpful in addressing spatial issues, some gather more temporal information, and others help local people to analyse their situation by ranking issues or problems. Just as care is needed when matching a research methodology to the kind of study being done, so within RRA the most appropriate tool is selected for each type of information needed to meet the study's objectives. RRA insists that diverse perspectives should be explored within the community studied. Villages, like other communities, represent many diverse interests depending on gender, social and economic standing, sources of livelihood, etc. It is important that the views of different groups and interests be explored in order to fully understand issues as complex as resource use patterns in a community. In short, the RRA method requires that a diverse group of researchers use a diverse set of tools to explore the diverse views and experiences of a community. This diversification of perspectives at the level of the researcher, the informant and the means of communication which links them together is called triangulation. Triangulation is a core principle of RRA because, on the one hand, it is the primary strategy used to avoid bias in the research results and, on the other hand, it considerably enriches the quality of the data collected. |

Following the RRA, a brief survey was conducted and questionnaires were administered to 30 randomly selected households in the community. Geo-reference points were also taken in each study area to tie the qualitative information to specific latitude and longitude points and to facilitate future monitoring of changes in the vegetative cover. In addition to these methods, follow-up focus groups and more in-depth interviews were carried out on topics identified as issues of particular importance in the RRA and secondary information was collected from a wide variety of sources.

This combination of methodologies permitted the team to use each method where it was the strongest. RRA, for example, is excellent at getting rich qualitative information and encourages the researcher to respond to local concerns and adapt the approach to local issues. It creates a rapport with the village that allows more delicate and controversial subjects to be broached in a sensitive and non-confrontational way. It is also particularly effective at probing deeply in order to understand why certain practices are followed and to explore the logic behind those practices. These are areas where questionnaires, which are often limited to close-ended responses, often cannot elicit good information.

RRA is not so effective, however, at gathering standardized information that can be systematically compared across communities or at different time intervals. This is where quantitative techniques-surveys for social science information and geo-referencing for monitoring the vegetative cover-can complement the qualitative and participatory approaches. The surveys assure that a certain core set of issues are approached in a way that permits systematic comparison of all the sites that comprise the data set.

This monograph presents a case study of a single Rapid Rural Appraisal. This RRA was the first activity in the year-long research project described above and preceded the research in the seven sites that were chosen later for more complete analysis. This initial RRA was carried out so that the team could practise RRA techniques and clarify the objectives and working hypotheses it would use during the remainder of the study. In the actual case reported here, then, RRA was used by itself and not in conjunction with either surveys or geo-referencing as would follow in the remaining sites of the study.

In the case study, the reader will find out first what the team had to do to prepare for the field study and then how diverse tools were used to gather different pieces of information that eventually fit together into a kind of jigsaw puzzle of tenure and resource management in the study village. In the resulting picture, the key issues confronting local resource management are clearly discernible.

Before the actual visit to the village for the field research in an RRA study, there are several preliminary steps that are critical to the success of the endeavour. These include setting clear guiding objectives that will orient the team's activities in the field, selecting the research team and identifying the site where the study will take place. In the particular study illustrated by this case, two teams of people went to two neighbouring villages. This was done in part to have a larger sample and in part to enable more people to be trained in the methodology. Since the activities and results of the two studies were very similar, only the case from the village of Anivorano will be reported on here.

In RRA, a key consideration in selecting members of the team is ensuring that the researchers bring diverse perspectives to the study. This is important for triangulation.1 Every person on a team has certain characteristics that make him or her, on the one hand, more perceptive to some kinds of information and, on the other, less adept at picking up other kinds of information. This can lead to biases in the information that is collected. For example, a team of only men may, without even thinking about it, put more emphasis on looking at how men use resources than what women do. A group composed only of social scientists may not even notice certain patterns, such as the absence of younger trees, that would indicate a problem with resource regeneration. Because of this, RRA makes a special effort to combine individuals with different backgrounds, training and skills on the same team. This helps both to neutralize the biases of individual members and to enrich the information that is collected.

The members of this particular team were selected in order to triangulate several factors. There was concern that the team reflect a gender balance, that not all members of the team come from the same ethnic group, that various social sciences and technical disciplines be represented and that at least some members of the team have prior experience using RRA and/or looking at tenure issues. As it turned out, although it was not a priority in selection, there was also an interesting age diversity since one of the team members was near retirement. It helped to have an "elder" among the team members.

The final selection of team members included people with the following characteristics:

In addition, a nanny accompanied the team to care for the team leader's year-old daughter. This duo proved a great help in facilitating the team's integration into village life and establishing the rapport between researchers and villagers that so enriched the findings of this study.

One of the first steps in an RRA study is setting the objectives for the research. The objectives focus the activities of the team and guide their questions so that at the end of the time in the field, they have spent the most time on the issues of greatest concern and have not wasted time looking at questions that have little relevance to the study. There is a caveat to this, however. The objectives are generally set by the research team before they ever arrive in the village. There may be issues raised by the community during the course of the research that do not figure in the original objectives. If the team, on careful reflection, believes these are relevant to the study at hand, they may amend or expand the objectives to include these concerns.

In this case, a preliminary draft of the objectives was prepared by a subgroup of the team that had particular experience in tenure and resource management issues. The subgroup reviewed objectives that had been used in similar studies elsewhere and looked at secondary information from Madagascar in order to identify issues that seemed relevant. They then proposed these draft objectives to the team, which had a chance to consider and revise them in a meeting before going to the field.

Before leaving for the village, the team agreed upon the following:

Theme: Study on Tenure and the Management of Natural Resources

General Guidelines Concerning all the Objectives:

Objectives of the study on Tenure and the Management of Natural ResourcesObjective 1:Describe the territory, taking into consideration the following questions:

Objective 2:Identify how the resources defined above (I) are used, with particular attention to the following questions:

Objective 3:Analyse how the community's resources are managed and who has (a) rights, (b) responsibilities and (c) decision-making authority for each of the following resources: land; forests, trees and their products, water, fauna, other.

Objective 4:Determine the mechanisms for the resolution of conflicts around natural resources.

|

Additional Objectives for a Future Study:

Although the team did not include it among the objectives, it did gather considerable background information on the community studied in order to provide a context for the more focused resource management questions. In a future study, it would be useful to make this objective more explicit, adding a first objective:

In addition, since the final report must include a synthesis of the findings, it makes sense to be explicit about this in the objectives as well. Hence, a final objective might be:

This case study was a first effort at training team members and testing the methodology that would be followed in subsequent sites where resource management arrangements around national parks were to be studied. For a number of reasons relating to time and distance, it was not possible to choose a site very near a park for this preliminary study, so the team chose villages adjacent to classified forest areas as sites that would face similar issues. Two forest areas within a day's drive of the capital, Antananarivo, were identified. By talking to project and government personnel who worked in both forests, the team was able to narrow its focus to one of the forests where questions of resource management were more controversial and potentially more interesting to study. In addition, the project working in the area was very interested in gaining information from the studies to improve its interventions in the area. The team considered this a high recommendation for the site, since the information would find some immediate use and could potentially benefit the populations participating in the study.

In the next step, detailed maps were used to identify the villages that have land around the classified forest. Project team members then went back and discussed specific villages with government foresters and project staff who knew the area well. The purpose of these discussions was to obtain a short-list of five or six villages that could be considered "representative" of the area. Villages that were unusually small, that were composed of an ethnic group that is rare in the area, or that were known to have serious internal conflicts were eliminated from consideration at this stage.

Having narrowed the list to five potential villages, during the week before the study was to take place the team sent two researchers and the translator to the villages themselves to gather information that the team could use in its site selection. The advance team visited all five villages, spoke in some detail to village leaders about the purpose of the study and how it would be carried out, inquired about their interest in participating and assessed whether the village was logistically prepared to receive a team of seven people for a week. By briefly discussing questions of resource use and management, the visitors were also able to get a sense of the issues that concerned the villagers. The village leaders were told that since, regrettably, the team could not visit all five villages, a choice of only two would have to be made. They would receive word within the next three days on whether the study would take place in their village and those selected would receive information on the arrival of the teams.

On the return of the advance party the team met and, from the information gathered in these preliminary visits, chose two villages for the study. The villages selected were Anivorano (the subject of this report) and Ambodigavo. Both were Betsimisaraka villages with populations of 300-500 people, well off the main road and adjacent to the Classified Forest of Ankeniheny.

The team met several times before it left for the field to review methodological issues. Secondary materials on tenure and the area to be visited were distributed among the researchers, and a day was set aside to discuss the literature and to think about issues that might arise in the field. The team carefully planned its arrival in the villages, deciding who would be responsible for the initial protocol speeches and discussing what message should be transmitted. The team also decided who would launch the first activity that would be carried out with the population (preparation of a village map) and drew up a checklist of issues to be covered.

A subgroup of the team was responsible for logistical preparations. In the preparatory visits to the village, the team emissaries had explained that the researchers would prefer to stay in the village and integrate as much as possible into the daily life of the community. The village leaders were asked whether they could suggest a place, or places, where the team members might stay, either a village house or a communal facility, such as a church or school. In Anivorano, the village offered two one-room houses, one for the women and one for the men. The team logisticians assembled enough mattresses, flashlights, bath buckets and other essentials as needed for a village stay. They also bought basic foodstuffs, which were given to the women in the village who had agreed to supervise the cooking during the team's stay. These women prepared the meals each day and were compensated for their services.

These preparations for the field study were carried out over a two-week period. By the end, the teams were ready and eager to begin the fieldwork, as will be described in the next chapter.

Every RRA comprises a period of preparation for the field study, a period of research in the field and a period of analysis and write-up of the information. The activities of the Anivorano RRA from preparation to write-up are summarized in figure 1. This chapter focuses on the middle box: activities in the field. The fieldwork in an RRA typically lasts from four to 10 days. During this time, the research team lives in the village (or villages) where the study is taking place and uses a variety of tools and techniques to gather information. Each bit of information is like a puzzle piece. As more information is gathered, the pieces begin to fit together to make a coherent picture inside the frame established by the objectives at the outset. While the fieldwork is often done during a single block of time, this is not always the case. The programme of the researchers or the villagers may determine a better schedule, such as three successive weekends of research. It does not matter how the fieldwork is timed as long as the essential methodological principles of RRA (e.g., setting clear objectives and the triangulation of team members, tools and informants) are rigorously followed.

The field research for this RRA lasted seven days; the first and last days were abbreviated because the drive to and from Antananarivo took several hours. Following a brief introduction containing information relevant to all the techniques used, the team's activities are described in detail in the following pages in the order in which they actually took place.

| PRELIMINARY ACTIVITIES | |

|---|---|

|

|

| ACTIVITIES IN THE FIELD | |

Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

Day 4

|

Day 5

Day 6

Day 7

SSI semi-structured interview |

| AFTER THE FIELDWORK | |

|

|

Figure 1: Overview of activities for Anivorano RRA on tenure and natural resource management .

Although detailed information on the village of Anivorano will be provided in chapters 4 and 5, the reader may wish to know a bit about the village in order to put the activities that follow in some context. Anivorano is a village of about 300 people, all of whom (with the exception of a very few recent arrivals) belong to the Betsimisaraka ethnic group. The livelihood of the villagers is oriented primarily around agriculture, and particularly the production of rice on steep hillside slopes around the village. The villagers live in small, usually one-room wooden houses built on short stilts to keep them dry. Many villagers wear clothing made of the area's characteristic cloth woven of reeds. Signs of traditional religious practices, such as remains from animal sacrifices, are seen throughout the village. A small school constructed of corrugated metal sheets perches near the church on a hill overlooking the village; the village water supply is obtained from a spring that surfaces near the school. Access to the village is by a winding laterite road that hugs the hillsides and becomes impassable during certain times in the rainy season. This is about as much as the RRA team knew about Anivorano as it pulled into the village on a bright sunny Thursday afternoon, ready to begin a lively week of field activities.

Good RRAs exude relaxation and flexibility. This does not mean, however, that they are sloppy or haphazard. On the contrary, no one can be relaxed who does not feel well prepared or is in a panic because the information being gathered seems incoherent. There are several procedures that are critical to ensuring that RRA's various activities are well prepared and that the information obtained is at least partially digested as the team progresses so as to avoid total confusion. These include carefully preparing an interview guide for each activity and spending the time to review each tool and discuss the findings as a group.

Before carrying out each of the activities reported in this chapter, the team met as a group to prepare a checklist (interview guide) of the issues to be covered in that session. This is an important step because RRA does not use preestablished questionnaires. Instead, the researchers follow question guides which orient the direction of the interview or activity but allow enough flexibility and open-endedness to ensure that villagers' concerns and perspectives shine clearly through. If interview guides are not prepared, or are too vague, the resulting information tends to be scattered and unsystematic. When this happens, it is often very difficult to assemble a coherent picture at the end of the fieldwork. If the guide is too focused, or if it is followed too rigidly, the team may fail to follow up on interesting and surprising avenues of inquiry. In such cases, the final picture risks reflecting the team's preconceived notions. Hence, there is a balance to be struck in preparing and following checklists.

Photo 1: This is a view over the village of Anivorano showing cleared hillsides, once forested.

Some of the activities were carried out by the whole team, with a group of village informants. In others, the team divided up and carried out different activities. Often this would involve doing the same matrix, or interviewing on the same topic, but with different groups of villagers. For example, one group might talk to women, while another met with men. This made possible a greater triangulation of perspectives and ensured that diverse viewpoints were represented throughout the research.

After each activity, the team met again to review what it had learned. If the team had split into subgroups, the researchers who had conducted the exercise first met together and noted the most important information that they had learned on a sheet of flipchart paper. They then shared the information with the rest of the team. If the whole team performed the activity together, it met as a group to prepare the flipchart of salient points. This "digesting" and sharing of information was time-consuming, but the team felt that it was well worth the time spent. As the information-gathering progressed, the teams noted where information had been triangulated by putting a red triangle next to information that had been cross-checked. Inconsistencies were marked with a green question mark so that the team would remember to pursue those issues further. By systematically reviewing the information as it was collected, the team was better able to prepare the next day's tools. Furthermore, the availability of flipcharts summarizing each interview greatly facilitated the analysis of information at the end of the study.

At some point each day, the team held an "interaction" meeting (usually in conjunction with the sharing of information), when it focused on methodological questions. During this time the team would review all the activities of the day and consider whether there had been problems with the comportment of team members or the use of the tools that could be corrected. It also thought about whether any biases had begun to creep into the study and considered what might be done to overcome those biases. Finally, it planned the activities for the next day, deciding what issues would be addressed, what tool was best suited for looking at those issues and to whom the activity should be oriented. At this point, the team prepared the checklist for the activity and selected one person to be the "presenter".

These interaction meetings often took as long as two hours, especially if there was information to be shared among different groups that had performed parallel activities during the day.

In this section a report of each day's activities is presented with a brief description of the techniques used and some of the most interesting information that resulted from the activity. The summary of findings is purely indicative; it does not attempt to summarize all the information collected and it avoids, for the most part, repeating when the same information was collected by multiple techniques. The reader should remember, however, that the repetition of information from different sources and using different techniques is essential to triangulation.

| DAY 1 | |

|---|---|

| Morning: |

|

| Afternoon: |

|

Activity: Protocol meeting with village

By whom: Whole team

With whom: The village elders and a cross-section of the village inhabitants (approx. 40 people)

Description: The protocol meeting was held in the village square, where it was accessible to anyone who was interested. The purpose of the meeting was to explain the purpose of the research so that the community would feel it had a stake in the research process.

The team explained carefully how the results of this and other studies would be used to inform a national policy dialogue on tenure and natural resource issues. The presenter noted that thanks to their taking the time to understand the situation of villagers like those in Anivorano, there was a greater chance that the villagers' concerns, and not just the views of the more rich and more powerful, would be represented in the debate. The team stated explicitly that the research was unlikely to lead to any immediate changes that would help the village in the short-run. Rather, the information gained would help in drafting laws that were more appropriate to the concerns of villagers like themselves.1

In addition to this discussion, the following points were covered in the protocol meeting. (Since the elders of the village had already heard much of this information on the occasion of the earlier visit to prepare the RRA, they were able to contribute to the explanations in many cases.)

Team Introduction. Each researcher introduced him/herself, including some personal information about family or interests (to try to "humanize" the team) and explained his or her particular research concern (to preview the kinds of questions that would be asked). A woman on the team mentioned, for example, that she had a special interest in how village women use and manage resources and would therefore be interested in talking to women about these questions and would like, if possible, in accompanying them to their fields.

Selection of the village. The selection of the village was explained, along with the concept of sampling. The idea that the team had "drawn the names of the villages from a hat" was presented to reassure the population that there was no negative reason that they had been selected and that it might as easily have been the village next door. This explanation was used to reinforce the message that the accuracy of the information was important since the results of the study would help in understanding not only their specific situation but also the issues facing other villages in similar settings.

Programme for the week. The general programme for the stay in the village was outlined (though it was not possible at this point to specify the exact programme for any given day). There was special mention that on the last day, before the team's departure, it would present the results of its findings so that everyone would have a chance to find out what the team had done and to correct or add any information as necessary. Once again, the notion of sampling was discussed in order to explain that the team would be performing different activities with various groups of people but that all the information would be brought together at the end. The team particularly emphasized the importance of getting the views of all different kinds of people in the community.

Confidentiality. Throughout the meeting, the team assured the villagers that nothing they told the researchers could bring them any harm and that the identities of individuals would not appear in any written documents or reports.

Activity: Participatory village and territory mapping

By whom : Whole team

With whom: All the villagers who had been at the protocol meeting and others who drifted in

Description: Since a large group of people had assembled for the protocol meeting, this provided the perfect opportunity to make a participatory village map. The map had several purposes. Among these were:

The team had decided to focus at first on obtaining information on the central, inhabited part of the village. This included locating important sites, including village infrastructures, homes of village leaders, other landmarks, water sources and others. Then, if time permitted, it would expand the area of inquiry to ask about the territorial limits of the village, uses of space, the origins of the boundaries, relations with neighbouring villages and more.

Principal findings

The map-making was a lively activity, with many different people contributing information and helping to draw the boundaries and identify landmarks. Because the central inhabited village is only used for a few months of the year (the rest of the time people live in houses they construct in their fields), the map rather quickly expanded to include all the lands that the village considers to be theirs (the "territory"). Among the key pieces of information that came out in making the map were the following:

The team made this map in collaboration with a large group of villagers seated on the ground in the village square. The outlines were drawn with a stick in the dirt, and stones, leaves and other objects were used to indicate important landmarks. Information about the dates when different parcels were cleared was gathered in a later activity (see day 6).

Activity: Guided village visit

By whom: Whole team (divided into three subgroups)

With whom: Three village guides

Description: By the time the map was completed, it was late afternoon. Most people needed to return home to take care of animals, prepare the evening meal and collect water. The team members were eager to get to know their adopted village a bit better, however. Dividing into groups of two, each pair asked someone with whom they had become friendly during the mapping exercise to show them the village and introduce them to people they met along the way. This made it possible to make contacts with people who had not been able to attend the formal introduction, helped to develop a rapport with both the guides and the people encountered on the route, and-although it was entirely informal-gathered considerable information about village social structure, history, customs and economic activity.

Activity: Team interaction

By whom: Whole team (moderated by the team leader)

Description: After dinner, the team met briefly to review how things had gone during the day, to share the information from our village visits and to prepare the checklist for the transect that was to be carried out the next morning. Minor difficulties that had arisen during the day (e.g., some team members had tended to ask leading questions during the mapping activity) were discussed, and corrective measures were suggested.

| DAY 2 | |

|---|---|

| Morning: |

|

| Afternoon: |

|

Activity: Transect walk

By whom: Whole team (divided into 3 subgroups)

With whom: Three men and one woman guide

Description: A transect is a guided walk across the full territory that permits the team to ask questions as it passes through different micro-ecological zones. To do this transect the team divided into three subgroups with two researchers in each group. Each group had a different theme: one group looked particularly at trees and forests, the second focused on land and agriculture, and the third investigated animals and livestock. Each group developed a checklist with questions relating to its theme. Since the team wanted to look at the interaction among all of these factors, it was expected (and desired) that there would be substantial overlap between the information gathered by the different groups. In this way some information could be triangulated from several different perspectives.

The day before, just after the mapping exercise, the team had discussed the upcoming transect with the participants and asked for "specialist guides", with particular knowledge of trees, agriculture, or livestock to accompany the team members on their walk. Three men and a woman had been selected by the villagers and they were on the team's doorstep by 7:30 on the morning of the transect. Each subgroup set off in a different direction, depending on where the guide proposed as the most interesting for their topic, but each was determined to reach the edge of the territory in whatever direction they walked.

Principal findings

The nature of the terrain made the transect something of a physical feat. The fact that each of the groups persisted to the territorial boundaries, through gullies and over hilltops, substantially increased the villagers' respect for their urban visitors. In spite (or perhaps because) of the difficulty of the hike, the groups came back with a wealth of information. As expected, there were many areas of overlap where information could be cross-checked by the different groups. In a few areas, the teams found contradictions and noted them so that the issue could be pursued further. The team forester, who had the best technical grasp of these issues, drew the transect diagram from information shared by the subgroups after the walk.2

The following summarizes a small portion of the rich information gathered during the transect walk:

This transect was drawn by the team forester following the transect walk when three subgroups of researchers went out in different directions with village guides to the edge of the territory. More descriptive information from the walk was compiled on flipcharts.

Activity: Semi-structured interviews with local administrators

By whom: One member of the Anivorano team and a representative of the RRA team that was studying the neighbouring village of Ambodigavo

With whom: Local (firaisana) government official

Description: During the time that the rest of the team was engaged in the transect one member went to the local administrative centre to interview the government official there. This purpose of this activity was two-fold: to gather information and to explain, again, the purpose of the study and the teams' activities in the firaisana (rural community). (These officials had already been contacted during the preliminary site visits.) The interview gathered information about the local administrators' views on land use in the villages, their role in encouraging or discouraging commercial exploitation of wood, their knowledge of tenure conflicts in the area and their role in resource management and conflict resolution. In addition, the interviewers discussed broader resource management issues in the administrative zone and tried to determine whether issues arising in the villages being studied could be considered "typical" of the area as a whole.

Activity: Team interaction

By whom: Whole team

Description: Once the groups had a chance to recuperate from their transect walk and had worked on their individual summaries of findings, a team meeting was held at the end of the afternoon to share experiences, consider where the information was leading, identify points that cross-checked or contradicted one another, and plan the next day's activities.

| DAY 3 | |

|---|---|

| Morning: |

|

| Afternoon: |

|

Activity: Semi-structured interview

By whom: Two team members

With whom: Commercial woodcutter

Description A chance early morning encounter with one of the three commercial woodcutters with permits to exploit the forest in Anivorano resulted in an impromptu semi-structured interview. Information was gathered about the people holding permits, some of the principal problems encountered by the woodcutters and how the forest is divided among the exploiters. While superficial, this information was at least helpful in assisting the team to prepare for more in-depth interviews that would take place later in the study.

Activity: Venn diagram

By whom: Whole team

With whom: Three men, one woman elder

Description: An appointment had been set for early on the third day to meet with four leading members of the village to do a Venn diagram. Three men and one older woman were waiting when the team got to the village meeting place. One team member began by explaining the purpose of the diagram. The respondents answered that they thought the activity was a useful one but that before talking about such issues it was only appropriate that all present should drink to the honor of the ancestors. The team leader quickly sent out for a bottle of rum and the meeting was appropriately inaugurated. (The team soon decided that it was prudent always to have a bottle of rum on hand since, as it turned out, a great many activities touched on subjects such as village history that entered the domain of the ancestors and therefore proceeded more smoothly when anointedÉ)

Photo 2: Villagers constructing a Venn diagram to show how village institutions interact with outside organizations.

Principal findings

The Venn diagram placed Anivorano in the context of the fokonolona (collection of villages sharing common roots) to which it belongs. Seven villages comprise the fokonolona and the Venn diagram clearly indicated the linkages between the various villages. Both traditional and modern administrative structures bring representatives from the seven villages together. Once the diagram was completed, the session evolved into a semi-structured interview on land rules and rights of ownership and use, using the diagram to indicate who makes decisions under different circumstances.

Among the key findings of the Venn diagram:

The Venn diagram was done with a group of village notables in the town square on a large sheet of flipchart paper laid on the ground. Papers of various colours and shapes were stuck on the flipchart to represent different institutions. The village of Anivorano is represented in the large circle at the centre of the diagram. Within Anivorano, the four principal authorities are represented by diamond shapes. Since the Tangalamena and President are both members of the Ray aman dReny (Elders), the diamonds overlap. In the larger circle outside the village limit but still inside the fokontany the six other villages are represented, each with their own leaders. The lines between the Tangalamena of the various villages indicate that decisions are often made in consultation. The group of Tangalamena is presided by the leader from Anivorano. Similarly, the President (PCLS) maintains contacts with the political committees of the other six villages, as indicated by the broken lines. He also reports to the PDS, a higher administrative authority based outside the fokontany.

Activity: Wealth ranking

By whom: Whole team

With whom: Two young men of village

Description: The team decided to do a wealth ranking, using cards with the names of each head of household, after lunch. One of the younger men of the village, who had already been helpful on several occasions and was generally friendly with the team, was invited to eat lunch with the team and then to respond to the wealth ranking afterwards. He brought a friend along. One of the team members had already obtained a list of the names and had prepared the cards.

After discussing his ideas of what "wealth" means in the community (principally cattle and land sufficient to feed the family), the respondent divided the cards into four piles. Later, a team member organized the information into the histogram in diagram 4, showing what proportion of the village falls into each group and the characteristics of the different wealth categories.

Principal findings

Among the key findings of the activity were the following:

First, cards bearing the names of each head of household were prepared. After discussing what "wealth" means, the informant put the cards in different piles so that all the families in a pile had approximately the same level of wealth. This diagram was later drawn by the team to summarize the information from the card piles.

Activity: Team interaction

By whom: Whole team

Description: Later in afternoon, the team had a meeting to review the findings of the wealth ranking and the Venn diagram. The group was pleased to find that many points had already-on only the third day-been triangulated thanks to using different tools and talking with different informants. Information about mechanisms for the distribution of land in the community, for example, had been cross-checked and complementary information had been gathered in the map, transect, Venn diagram and wealth ranking. With each activity, the team's understanding of the rules concerning land allocation and their significance increased, enabling the researchers to ask more focused and pertinent questions as the study progressed. On the question of bias, there was some concern that certain village leaders had begun to dominate the activities. The team decided to put more effort into ensuring full participation of a wider range of villagers. One strategy for doing this was to move activities away from the central square and to do them instead with selected families or smaller groups in more out of the way places.

Activity: Semi-structured interview

By whom: Four team members

With whom: President of the youth group

Description: After dinner, several members of the team went to play cards with the President of the youth group. They had prepared a list of topics they wanted to discuss with him, but decided not to conduct a formal interview where information would be noted as they went along. Instead they discussed, played, joked and talked about many subjects including most of the ones on the checklist. Afterward they wrote down the information that was pertinent to the study.

Principal findings

Several important issues not previously covered by research activities surfaced in this informal gathering focused on youth concerns.

| DAY 4 | |

|---|---|

| Morning: |

|

| Afternoon: |

|

Activities: Semi-structured interviews (4)

By whom: Team members (divided into groups of two to three)

With whom:

Description: The fourth day of the RRA in Anivorano fell on a Sunday. Since some members of the village attend church and others do not, it was decided not to schedule any large group activities, but rather to divide the team into subgroups and to pursue some of the more focused questions that had arisen out of previous activities. One group attended the village church service, after which they interviewed the church leader and members of the congregation. Another interview with the security officer triangulated information gathered in the Venn diagram. One group spent the morning with the women who did the cooking for the team and was able to gather information on women's rights to land and other resources. In the early afternoon, a historical profile was done with several elderly villagers. This was not a detailed historical interview, but rather a chance to identify major periods in the history of natural resource management in the community. This information was needed to prepare the historical matrix that would be completed later in the day.

Activity: Historical matrix

By whom: Whole team

With whom: Large mixed group of villagers

Description: The purpose of a historical matrix is to see how certain factors have changed over time and to try to understand how communities adapt their strategies and activities to changing circumstances. This matrix was traced on paper, with five historical periods (ranging from the era before the revolution of 1947 to the present) along the horizontal axis. The vertical axis had 13 variables that were derived from previous discussions. These were either indicators of how resource availability and use have changed or indicators of the impact of those changes on the well-being of the community.

The historical matrix was slow to get started. People drifted in and the team became worried that if it began too late, participants would leave for the evening meal before the activity was completed. As it turned out, it was necessary to bring lanterns to complete the matrix, but this did not deter participation. People found the process so interesting that not a single person left, and in fact many more people joined the group as the discussion became more animated.

Photo 3: While doing a historical matrix villagers are identifying events which show how use of resources has changed.

Principal findings

The historical matrix (diagram 5) clearly showed the pressures of increasing population (and food cultivation needed to support that population) on a fixed land base. In addition the following trends were clearly noted:

The historical matrix was drawn on a large sheet of paper on the ground in the central square. Room was left at the bottom so that respondents could add additional variables. They added the mine exploitation category. Symbols or pictures were drawn next to each variable to assist the illiterate. The matrix was completed vertically (completing one time period before starting the next), with the villagers placing beans in each square to indicate the importance of each variable during the time period in question. In almost all cases, the respondents came to a consensus on how many beans should be placed in each box. This was not the case concerning well-being, which provoked a major argument. The team members noted the diverging points of view even though only one viewpoint showed up on the matrix.

| DAY 5 | |

|---|---|

| Morning: |

|

| Afternoon: |

|

Activity: Preliminary analysis

By whom: Whole team

Description: On the morning of the fifth day, the team scheduled no information gathering activities, but instead took time out to reflect on where it was in the research process. This involved, first, sharing information from activities that had not been done as a group and had not yet been fully processed. Then the team reviewed each of the objectives in turn, noting the most significant findings on flipcharts. Lists were also started to note areas where the team felt that information was missing and where information was contradictory or unclear. The team took particular pains to review whom their informants had been during the first four days so that if there were any biases they could compensate in the last activities. While no acute imbalances were noted, the team did decide to orient some more sessions towards women and to ensure that at least a couple of the interviews took place with families that had been identified as among the poorest in the wealth ranking.

In light of this careful reflection, the team sketched out a programme of activities for the last two and a half days in the village. Having identified the issues still to be addressed, it considered which tools would be most effective at getting the information. It then chose the participants for each activity in light of its review of possible informant biases.

Activity: Two semi-structured interviews

By whom: Team (divided in two groups)

With whom:

Description: Semi-structured interviews were carried out with a poorer couple and with two older women, primarily to triangulate information on resource use and tenure rights that had been gathered in earlier activities. This enabled the team to find out what happens to widows, how resources are shared within families and what happens when landholders leave the community.

Activity: Family economy matrix

By whom: Team (divided into two groups)

With whom:

Description: The team had by now identified the various forms of resource use in the community but felt that it was still unclear about the relative importance of those activities. This information was needed to understand what factors were driving the overall exploitation of resources, and particularly the clearing of new lands in the forest. It decided to do a family economy matrix with several different families to get a better sense of the importance of different elements of the household economy. The matrix showed different elements of the household economy on the vertical axis. On the horizontal axis, it then compared the importance or each activity according to whether it was consumed by the family or sold. Each family also estimated, overall, the relative importance of each activity in its livelihood.

Family economy matrices were done with several families, including one that had been identified in the wealth ranking as among the poorest. This is the example from one family. The matrices were drawn on flipchart paper, leaving room for each family to add additional variables. First, the first two columns were completed horizontally, as the respondent compared whether the product was mostly sold or mostly consumed at home. When all the variables had been completed, the last column was completed vertically. The respondent was asked to compare the relative importance of each of the variables in the overall family economy.

Principal findings

Activity: Two semi-structured interviews

By whom: Team (divided into two groups)

With whom:

Description: One of the village shopkeepers had been outspoken in several of the group activities on environmental issues and his concern about the destruction of the village's forest reserve. Two members of the team interviewed him at length one evening in his shop and learned more about the history of the villagers' attempts to control commercial woodcutting and why they had largely been unsuccessful.

The team also made contact with a "poacher". This was one of the younger men of the village, who had cleared village forest land for his personal fields without following the norm, which requires a community decision before forest can be cleared. The interview explored the reasons why young people are pushed to clear forest lands, the sanctions they face and the frequency of the activity. This interview, like several of the previous ones with village youth, was conducted in a very informal setting and was interspersed with much joking and camaraderie. This was particularly important given the sensitivity of the topic.

| DAY 6 | |

|---|---|

| Morning: |

|

| Afternoon: |

|

Activity: Historical analysis of the territory map

By whom: Whole team

With whom: Group of elders, one woman, one youth

Description: The first day, when villagers drew the map on the ground, team members copied the map first into their notebooks and then onto a large sheet of flipchart paper. Since the map clearly indicated 16 different cultivation areas in the Anivorano territory, the team decided to use the map to explore deforestation patterns further. Working with the map, team members asked a group of more elderly informants to indicate when the different areas had been cut and to describe the circumstances surrounding the cutting. This led to an extremely interesting discussion that triangulated information previously collected in the Venn diagram, transect and other activities; it also added considerable new information and clarified several issues that had been unclear.

Principal findings

Photo 4: Bean quantification is being used to show the impact of the rice production cycle on soil quality.

Activity: Bean quantification of tavy cycles

By whom: Whole team

With whom: Same group as above

Description: The technique known as "bean quantification" can be used whenever researchers want to quantify (by rough proportions) the size or quantity of variables under discussion. In this case the technique was applied to understanding how much land of different soil qualities exists in the village territory. The historical mapping served as an excellent stimulus to a broader discussion of environmental issues, particularly soil degradation and the effects of deforestation. Team members always carried a small sack of beans to use as counters. In previous discussions they had learned that the village had a name for the most highly degraded soil. Taking a pile of beans to represent all the land of the village, they asked their informants to show what portion of the soil was the most severely degraded type. This done, they then asked what portion was the best-quality soil, which had another name that had been noted earlier by team members. Having launched the discussion with these simple questions (but having very little idea of where it all would lead), the team then sat back with astonishment as one of the informants said, "And let me show you what the rest of the soil of the territory is likeÉ". He proceeded to divide the remaining beans into seven different soil-quality types, each distinguished by the kind of plant that would regenerate there if the soil was left fallow.

Then, using the different piles of beans, he described the production system that causes the soil to degrade, starting with high-quality soil in the forest. He showed how over half a century, with 10 rice production cycles (each cycle comprising one rice crop and five years of fallow), the soil degrades to the poorest soil type. Soils of this type require a fallow period of more than 50 years to regenerate to the quality of soils found in secondary forests.

Diagrams 7 and 8 were drawn from information gathered in a semi-structured interview using bean quantification. First, a mound of beans was divided into piles of different sizes to show how different types of soil are distributed around the territory. The informants then described, by pointing at the bean piles, the process by which good soils degrade over time when rice is produced. The informant then reformulated the piles to show the amount of land of different quality 40 years ago. These diagrams were drawn by the team to summarize the information from the bean quantification exercise. They were later verified with the informants who had provided the initial information.

This diagram summarizes part of a discussion using bean quantification. See diagram 7 for explanation.

He next proceeded to place a few beans (ranging from one to 10) next to each of the soil types. These beans represented the relative yields of rice on each type of soil. The most productive land was shown to yield 10 units from a parcel of a given size, while the poorest land would only produce 1 or 1.5 units on a parcel of the same size.

Finally, the informant was asked to choose a reference point in the past (he chose his wedding date, approximately 40 years earlier) and to indicate the amount of land in each soil type at that time. He re-sorted the bean piles to respond to this question. This enabled the team to see how the clearing of the forest and the cycle of rice production has caused a notable deterioration in the overall quality of soils in the territory over the 40-year period.

After returning from the interview, the team took several hours to organize and digest all the information that had come out of the discussion and to represent it (see diagrams 7 and 8 above). These visualizations were later verified with the informant.

Activity: Wealth ranking with poor family

By whom: Whole team

With whom: Very poor family

Description: In the afternoon, the team walked to the household of a family ranked among the poorest in the first wealth ranking. The family lives in its fields at the edge of the village, almost beneath the spray of a massive waterfall. The walk passed through several cultivation zones that had been deforested at various times in the past. On the basis of information gathered in the morning, the team was able to identify clearly vegetation patterns that differed depending on the quality of the soil and the number of times it had been cultivated.

The family had been advised in advance of the team's arrival and were pleased that the researchers had made the effort to reach their remote compound. The information from this family largely triangulated what the team had learned in the first wealth ranking, reemphasizing that access to land is a function of the ability to mobilize labour. This labour may come either from the family or from other villagers who are paid to help during critical labour bottlenecks.

Activity: Team interaction

By whom: Whole team

Description: The team spent the sixth-day interaction meeting discussing its initial hypotheses concerning resource-use patterns and the causes and consequences of environmental degradation in the territory. It also reviewed information it had gathered on property rules and the potential impact of individual titling. The purpose of these discussions was to clarify the issues sufficiently so that the team could present a coherent feedback of information to the village the following morning. All charts and diagrams were assembled and tasks were divided so that each team member would present a topic, using the diagrams to illustrate the points to be discussed. Each person prepared a presentation and verified the main points to be covered with the rest of the team.

| DAY 7 | |

|---|---|

| Morning: |

|

Activity: Village feedback meeting

By whom: Whole team

With whom: Cross-section of village (about 50 people)

Description: The entire village was invited to the feedback session on the last day of the team's stay in Anivorano. A wide cross-section of people attended, including men and women of all ages. The meeting was held in the village square where many of the other activities had taken place. Rain later forced the assembly to take refuge in the house where the team had been staying.

The feedback meeting sought to present information that

Photo 5: In the feedback meeting, the information collected during the study is verified.

The population showed great interest in the results of the study and seemed to feel that the team had captured the key issues well. Several minor amendments and corrections were offered, which reassured the researchers that the audience was listening with a critical ear and not just agreeing out of politeness.

Two members of the team expressed thanks to the whole village and explained again how the information from the study would be used and what the team would be doing next as it continued similar studies in other regions of the country. Three kinds of rum appeared as if from nowhere, and villagers and team members shared a last libation before bidding one another a fond farewell.

After the team's return to Antananarivo, the members divided up the objectives so that one or two people worked on organizing information under each objective. The large flipcharts where information had been summarized after each field activity were cut up and arranged by objectives around the wall of the meeting room. These subgroups worked for two days and, on the second afternoon, the team reconvened to consider the information collected. Each group or individual presented a detailed outline of his or her section. Where information was missing, other team members helped to complete the outline; it was also easy to see where there were overlapping sections so that the duplications could be eliminated before the final paper was written.

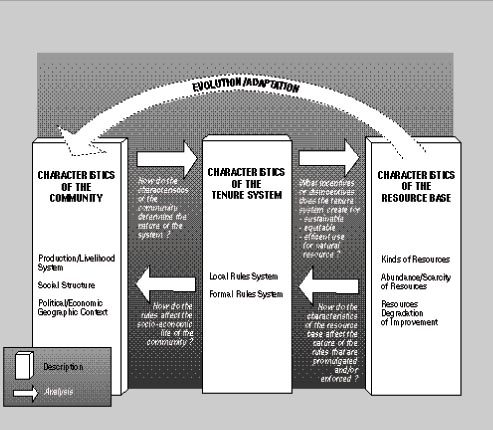

As the group worked on these questions, it realized that a last synthesis chapter was needed to capture the overall findings of the study and to summarize the causes and consequences of land degradation. An analytic framework (figure 2) was developed to push the team to think through the implications of the vast amount of information that had been collected during the field study. The framework organized the descriptive information under three categories: (1) characteristics of the community (including production systems, social structures and the political, economic and geographic context), (2) characteristics of the tenure system (both customary and state rules systems) and (3) characteristics of the resource base (including the kinds of resources, their abundance or scarcity and an evaluation of whether they are degrading or enriching).

Having organized the information according to these categories, the framework then pushed the team to use the information to explain why the community uses resources the way it does and to reflect on the implications for sustainable resource management. The team asked itself, for example, what characteristics of the community were important in defining the village tenure system and how, in turn, the tenure system (including external rules) affected the life of the community. Similarly, the tenure system has characteristics that create incentives (and disincentives) for how resources are used. Does it encourage or discourage the use of resources in a sustainable, equitable and efficient manner? How does the nature of the resource base influence the tenure system? As resources become more scarce, for example, is the tenure system adapting and are use rules becoming stricter?

The next two chapters discuss these questions, pulling together information from all the activities carried out during the seven-day field study of tenure and resource management in Anivorano. Chapter 4 is largely descriptive, looking at the community, its resources and the tenure/resource management systems used by the community to manage its resources. Chapter 5 then focuses on the analytic arrows linking the descriptive boxes in the model below and considers the implications for sustainable resource management.

This model was conceived by the team during the analysis phase of the study and was used to organize the information gathered during the fieldwork.

Anivorano lies 158 km southeast of Antananarivo in the province of Tamatave, the fivondronoana (department) of Moramanga, the firaisana (district) of Lakato and the fokonolona (rural community) of Anivorano. It is the largest hamlet in its fokonolona and serves as the administrative centre. Six other villages comprise the fokonolona with Anivorano. The village perches on a hill and is surrounded by an undulating territory that drops steeply away from the inhabited part of the village. This settlement is occupied for only a few months of the year (June to September), when the villagers return to live in a nucleated community. For the remaining nine months of the year, villagers disperse to live in small houses they construct in their fields, leaving only a skeleton population to assure the security of the core village.

Significant in the landscape is the new (1992) laterite road that winds perilously across the hillsides from the main road at Moramanga and continues a few kilometres beyond Anivorano to Lakato, where the lowest-level government officials are based. Before the road was built, Anivorano was served by only a track and was isolated from most outside commercial interests. Since the coming of the road, several shops have opened in the village, bringing outside residents into the community for the first time. Trucks now ply the road between Moramanga and Lakato, stopping at villages to pick up wood that has been harvested from community lands for export to the cities of Madagascar and to more distant destinations, including Japan. Before the road, commercial exploitation of Anivorano's resources was limited to intermittent attempts at mining beryllium and quartz. Now, three outside woodcutters have obtained government-issued permits to exploit the village forest, and a mine has been reactivated. The village is still vulnerable to isolation at times of the year when heavy rains make the road impassable.

The residents of Anivorano are all from the Betsimisaraka ethnic group, with the exception of the few outsiders who have come to live in the village for commercial purposes since the opening of the road. The village is approximately 200 years old and has a population of about 300 people, all of whom are descended from the same ancestors. The village is now divided into four sub-families. The common origin of the village population is a key factor in the success of the social cove-nants that govern tenure and resource management practices in the community.

Anivorano is also related by blood ties to the other villages in the fokonolona. These villages have, at certain times in their history, formed a single community while, at other times (such as the present), they have separated into distinct hamlets. The land that comprises the current village of Anivorano is, from the point of view of village residents and neighbours, clearly defined by known territorial boundaries and has been passed on from the ancestors who served as the root stock for the current village population.

Two different but complementary socio-political structures govern life in the village and larger fokonolona: indigenous institutions reflecting a long village tradition and outside institutions created by government decree. (See diagram 3: Venn.) Traditional village structures are active and dynamic. At the apex of these traditional structures is the Tangalamena (traditional religious leader), who is considered the intermediary between the living population and the village's ancestors and is responsible for maintaining ancestral customs and serves as president of the village tribunal. He carries a red cane to represent his authority. At the right hand of the Tangalamena serve the Ray aman dReny (RAD), or village sages, respected members of the community, either men or women and usually but not always elderly. The RAD advise the Tangalamena on issues of village importance, organize village events, such as community work days, and play a key role in mediating disputes.

The RAD and Tangalamena of Anivorano and the other six villages in the fokonolona frequently interact. They meet regularly to plan common village activities and to resolve conflicts that surpass the limits of any one hamlet.

In addition to the traditional authorities, government-mandated administrative structures also function at the village level. The village has a security officer (quartier mobil), a political "committee" and a President (PCLS) who reports to the authorities at Lakato.

The interaction between customary and administrative authorities is illuminating. The villagers recognize a clear set of administrative functions and responsibilities mandated by the State. These require, in some cases, skills (literacy) or capabilities (to travel) that would be beyond the capacity of traditional leaders. But at the same time, the population has been loath to see the State create parallel structures that might usurp the traditional authority handed down from the ancestors, who play a critical role in Betsimisaraka life. The local solution has been to integrate the two systems and largely co-opt the state structures into the customary arrangements. Hence, the government structure's PCLS has been made a member of the indigenous RAD, even though he is considerably younger than the norm for such elders. In this way, he is under the influence and tutelage of the traditional village leadership as he carries out his modern administrative functions. This is just one of several indicators noted during the study of the continuing force of these traditional structures, essential elements in the maintenance of effective customary tenure systems.

The youths of the village are frustrated by the limited role they are accorded in decision making where the RAD are clearly ascendant. The youth organization is largely devoted to carrying out plans initiated by their elders. While the RAD are officially charged with the task of conserving the resources inherited from the ancestors, there were some indications that their interest in reaping short-term benefits may temper their zeal to protect resources for the future. For example, as influential people, they can ensure that their sons get jobs with the commercial forest cutters. Some of the village youth, who have a longer time horizon than the elders, seemed more systematically to espouse conservation and sustainable development principles. Their views are given little weight, however, in village decision making. One consequence is that some youths, frustrated by the elders' failure to control the exploitation of community resources by outsiders, have begun to "poach" these resources themselves. In this way they ensure themselves at least some short-term benefits since they have little hope that the resources will last into the future.

The household economy for a typical family in Anivorano receives revenues (and goods in kind) from agriculture, forest exploitation and mining. Almost all families have at least some revenues, though perhaps small, from each of these sources. For most, agriculture is the principal pillar of their livelihood (see diagram 6: Family economy matrix). Only some very young families with few or young children relegate farming to a secondary position while the male head of household earns wages from forest cutting or mining.

Agriculture is centred primarily around the production of upland rice on the slopes around the village. Villagers try to produce as much rice to meet the family's needs as they possibly can, given labour constraints. Some small portion of the rice harvest may be sold to meet urgent cash needs, but most of the rice harvest is consumed. To the extent that there is a shortfall in rice production, revenues from cash crops are used to purchase the remainder of the family's cereal requirements.

Other hillside plots are devoted to perennial crops, including coffee, avocados, bananas and diverse fruits. Manioc is also planted in these fields. These crops are partly used for home consumption and partly sold.

To understand resource use in Anivorano, it is critical to understand, first, the primordial role of rice in the village economy and, second, the peculiarities of the rice production system on the steep slopes that make up the village territory. The land area suitable for lowland, irrigated rice production is infinitesimal and insufficient to provide even small plots to each of the families in the village. In the past, this land was cultivated, but the irrigation system that serviced the rice fields was destroyed by a landslide in 1972. It was never replaced because cost of repairing a system (originally installed by outsiders) of such limited benefit was too high. Since that time there has been no irrigated rice production in Anivorano, and the population has had to rely on upland, hillside rice.